Rules: What Rules?

This is not an article with strict rules about how one must frame photographs. Rather, it is about proportions and space, and it explains some things that have been discovered about them.

But in the end, what anyone likes is a matter of personal taste, and as the saying goes, there is no accounting for taste.

Which is not to say that there are no rules. There are classical design rules, and some people believe that the reason the classical design rules are as they are is because their appeal is hard-wired into our brains because of the way the world around us is constructed.

Or to put it another way, there is evidence of ‘rules’ of composition throughout nature, and these may explain why an extended form of these rules exists in classical art and design.

The Fibonacci Series in Nature and Classical Design

The Fibonacci mathematical series is simple. Start with 0 and 1. Add them together. Add the answer to the larger of the two numbers that have just been added. Repeat, and repeat, and repeat:

0 + 1 = 1

1 + 1 = 2

1 + 2 = 3

2 + 3 = 5

3 + 5 = 8 etc.

And as the series progresses, two things become apparent.

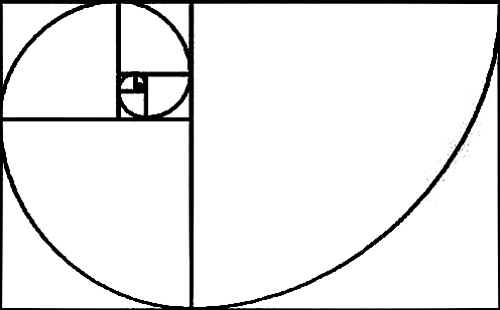

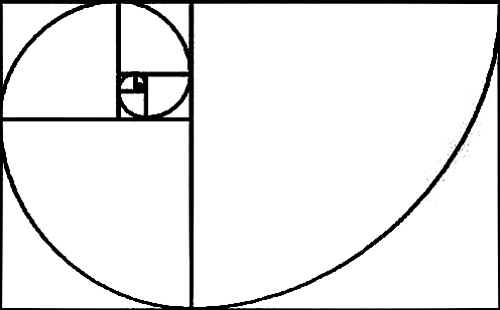

The first is seen if we construct rectangles with sides that are in the ratios of the series (1:1, 1:2, 2:3, etc) and set them one on another, and draw a line that curves to follow the corners of the rectangles, it forms a spiral.

And that spiral is echoed in nature in seashells and fruit and flowers and endless features of the natural world.

The second interesting thing we can see as the series progresses is what happens to the ratio of the larger number to the sum of the larger and smaller numbers, .

In the example above we only got as far as 5:8, but if we keep going, the ratio approaches that described and used in art and architecture throughout history certainly back to the Ancient Greeks, and which is known as the Golden Section.

Another way to express it is Phi (pronounced Fee), which is 1.618.

Run That By Me Again

Let’s imagine we have a rod colored yellow. We divide its length by Phi (1.618) and make that the length of the longer part, which we color red. The Golden Section is the ratio of the red part to the whole rod (the red part plus the yellow part).

And that relationship is used over and over in what is known as the classical tradition of design in art and architecture.

Turn the two parts of the rod at 90º to one another and we have the proportions of a room, or a picture frame.

Frames Today

Now fast forward to today. A glance at the picture frames on sale in any store will reveal that they come in long and thin, short and squat, and every ratio in between. Painting themselves come in all sizes and shapes, also.

Photography Today

Even between different cameras (both film and digital) there is a variation in the ratio of the longer side to the shorter side of the film or of the image sensor, and hence in the appearance of the image they capture.

For example, the proportions of the frame of the film for a 35mm film camera – the kind that has been around since the original Leica made by Oscar Barnack at the start of the 20th century, is 3:2.

The film for medium format film cameras used by dedicated amateurs and some professional art photographers comes in a variety of sizes, and the proportions of the frame of the film might be 3:2, or 4:3, or 1:1 or 6:7.

And for large format cameras the proportions might 3:2, or 5:4, or any of a number of other more arcane proportions.

Digital Camera Sensor Formats

This variety of formats is found in digital cameras also. The sensors in ‘Point and Shoot’ compact cameras are usually in the proportions 4:3. But there are some compacts that have sensors in other proportions, such as 16:9.

The sensors in Digital SLRs (single lens reflex cameras) are usually 3:2.

So whether starting with film or digital images, the variety of formats means that as often as not the starting point (the image itself) is not in the proportions of the classical tradition.

The Mounting Mat

When the photographic image is printed, however, the printer has a choice because he can print the image with or without a border.

And when the framer frames the image, he has a choice because he can set the image within a mounting mat of any size and proportions he chooses.

We may choose to follow rules of classical proportions or we may choose some other proportions. Whatever we decide, we have the opportunity to surround and set off the image and make it look more pleasing to our eyes.

Whereas if we print the image so that it fills the space right to the edge of the paper and if we do not use a mounting mat, then we have no choice about the proportions of the frame. Instead, the frame has to sit tight around the image.

It is not inevitable that the image will look less pleasing that way, but by doing away with the border and the mat we simply don’t have the options that we do with border or with a mounting mat or both.

Choices

What constitutes pleasing composition, proportions, framing, and space is subjective. And there is no accounting for taste. Having said that, these few opinions may help.

An image set within a wide mat makes the image look sumptuous and treasured.A thick mat with a bevelled window looks a lot better than a mat made of thin paper.

Setting the image just slightly above dead center can help prevent the image looking static or top heavy.

Approximately one woman in a hundred is color blind. The proportion is higher for men at approximately eight men in every hundred. And most people with color blindness are not aware of it.

The most common kind of color blindness affects the ability to distinguish red and green. Other people have trouble with shades of blue and green.

It’s probably wise to choose a color for the mounting mat that registers as little as possible so it doesn’t clash with the image. Off-white is a good choice.

Frames are more problematic and an idea of how the complementary colors work together will help. The make-up counter at a department store contains a lot of information about color combinations, as do art galleries.

Galleries

From about the end of the 19th century, artists often integrated the frame into the painting and it became an extension of it. It’s easy to overlook the frames. Now you may enjoy seeing paintings and their frames in galleries and see them in a whole new way.